Frequently Asked Questions

Questions about Grizzly Bear Biology & Ecological Value

Why are grizzly bears important?

Grizzly bears are culturally and spiritually significant to Native American and First Nations communities throughout the U.S. Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. Grizzlies are seen as teachers, guides, and symbols of strength and wisdom to indigenous peoples. They are a regional icon, a symbol of wilderness, and a key part of our natural heritage.

Grizzly bears are considered an “umbrella” species, and they play an important role in healthy ecosystems. Habitat that supports grizzly bears also supports hundreds of other plants and animals and human needs like clean water, healthy forests, and quality outdoor opportunities. Grizzly bears provide a yardstick with which to gauge the health of our wild lands.

Like all native species grizzly bears play a critical ecological role. They spread seeds from plants on which they feed, like huckleberries, and in some areas distribute marine or aquatic nutrients from fish including cutthroat trout and salmon. Their prolific digging for bulbs and burrowing rodents help aerate soils and their defecations help fertilize meadows, particularly in mid and high-elevation habitats.

Grizzly bears have been part of the Pacific Northwest landscape for thousands of years. We have an ethical and legal obligation to restore this and other native species. Grizzly bear recovery in the North Cascades is an important part of national efforts to restore endangered animals where suitable habitat still exists.

What do grizzly bears eat?

Grizzlies are omnivores. Like humans, they eat both plants and animals. They are also opportunists, taking advantage of whatever is available. Generally, less than 20 percent of a grizzly bear’s diet is meat. Most of their diet is from vegetable materials such as berries, roots, and grasses. They also scavenge meat from winter-killed animals, dig for rodents, and eat termites, ants, grubs, and other insects. If the opportunity arises they can become adept at fishing and hunting.

Because they must live off stored fat for three to six months of the year, they eat large quantities in summer and fall. An adult male may consume the caloric equivalent of ten huckleberry pies per day during the height of the berry season.

How long do grizzly bears live?

The average life span of a grizzly is 15 to 20 years. The oldest wild grizzly bear ever captured in North America was a 34-year-old female. However, grizzly bears are particularly vulnerable as cubs, with only half of cubs surviving past their first year.

How fast do grizzly bears reproduce?

Grizzly bears are the second slowest reproducing land mammal in North America, after the Musk Ox. Female grizzlies usually begin to mate at five to six years old and have on average two cubs. Cubs are born in the den in late January. They are helpless and weigh less than a pound and about half of cubs survive past their first year.

Grizzlies have cubs every three years on average. Cubs accompany their mother until she has another litter. Grizzly bear mothers are highly protective of their young and will risk death to protect them. Male bears do not participate in caring for the young.

How much space does a grizzly bear need?

A grizzly bear’s home range size depends on the richness of the habitat in bear foods. Grizzly bears are not territorial. They do not stake out and defend a well-defined area but follow food availability. Food sources are generally seasonal which forces bears to use different elevations and habitats. A grizzly’s daily movements may vary widely by season, food availability, age and sex of the bear, security cover, and level of disturbance.

The average home range size throughout North America for an adult female grizzly bear is about 70 square miles. Adult males have much larger home ranges, often 300-500 square miles and the home ranges of several bears could overlap. Research is needed to learn about grizzly bear home ranges and habitat use in the North Cascades.

Questions about the North Cascades

What is the North Cascades Ecosystem and Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone?

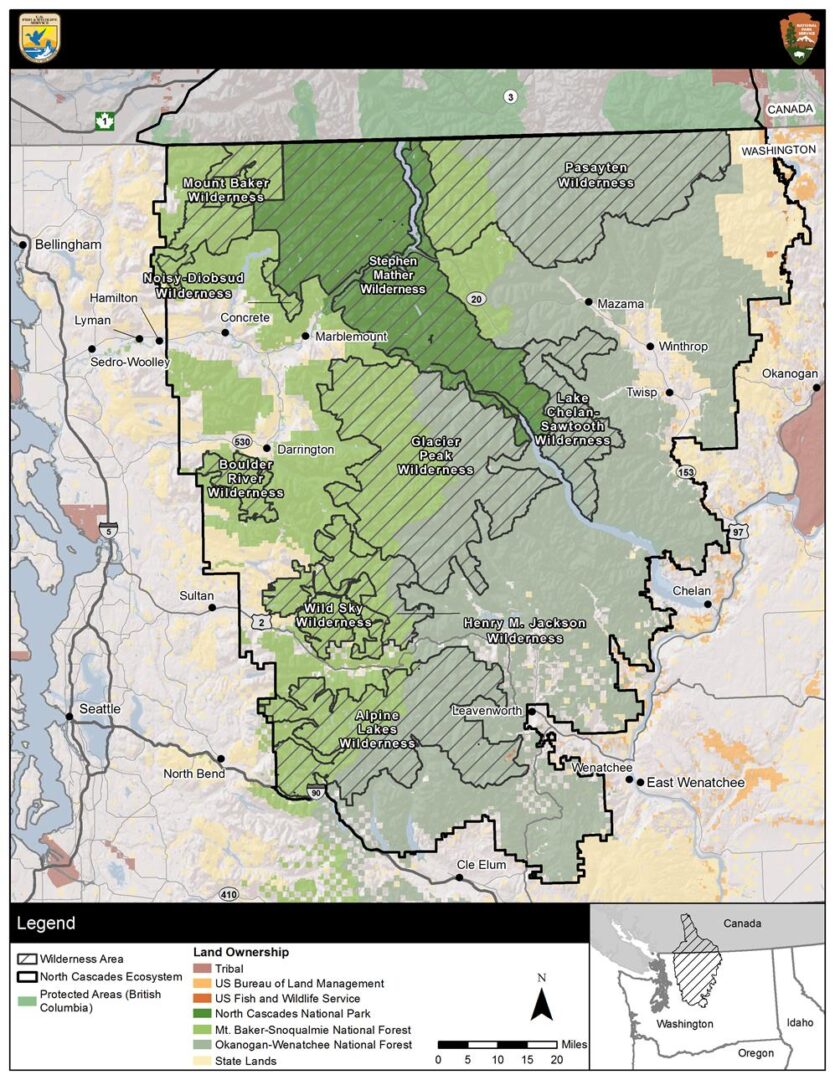

The North Cascades Grizzly Ecosystem is one of the largest contiguous blocks of Federal land remaining in the lower 48 states, encompassing approximately 9,800 square miles within north central Washington. Stretching from the US-Canada border south to Interstate 90, it includes all of the North Cascades National Park and most of the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie and Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forests. The ecosystem has been identified as a suitable recovery zone for grizzly bears because it has enough space, food, and wildness to support a grizzly bear population.

Ninety-seven percent of the U.S. portion of the North Cascades GBRZ is publicly owned land:

Do grizzly bears live in the North Cascades today?

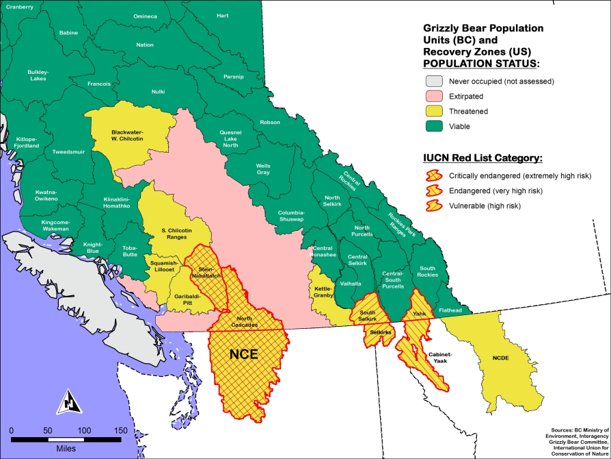

Federal agencies believe grizzly bears have been functionally extirpated from the North Cascades, with no evidence of reproduction or a survival population. The 2012 estimate for the Canadian portion was six bears. Because of their small numbers, they are widely believed to be the most at-risk grizzly bear population in both the US and Canada.

The most recent confirmed observation of a grizzly bear in the U.S. Cascades was in 1996. Efforts during 2010-2012 to locate grizzly bears remaining in the U.S. portion of the ecosystem using barbed wire “corrals” to capture hair samples for DNA identification yielded no confirmed grizzly bears; however, less than a quarter of the ecosystem was sampled. There may be a small number of grizzly bears still living in Washington’s North Cascades, but exactly how many is unknown, and they do not represent a population.

One grizzly bear has been confirmed during the past five years in the British Columbia portion of the North Cascades, within 20 miles of the U.S. border.

Why should grizzly bears be restored to the North Cascades?

Humans functionally removed grizzly bears from the North Cascades by hunting, trapping, and poisoning them. Killing off grizzly bears served an economic purpose at the time, but it eliminated an important cultural and ecological fixture of the landscape.

As we confront climate change and massive loss of species and biodiversity, restoring a viable grizzly population will contribute to the health of the ecosystem and benefit human beings and other species. Restoration of the grizzly bear would return the North Cascades to its natural state, a wild landscape that would include all the major species known to be native prior to European settlement.

Grizzly bears in the lower 48 states currently exist in only two percent of their former range. There are very few remaining places wild enough to support grizzlies. Restoring a healthy population of grizzly bears to the North Cascades is part of a national grizzly recovery strategy and vital to the conservation of the species in general as it will increase their geographic distribution and genetic diversity.

Can the North Cascades support grizzly bears?

Yes – wildlife biologists have determined the North Cascades can support a target population of about 200 bears, and probably more. There is plenty of protected public land, key foods, and low-road density grizzly bears need to survive.

Biologists created a recovery plan for grizzly bears in 1982, with individual “chapters” for each of the four recovery areas where grizzly bears currently live or occurred in the recent past, including the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, Bitterroot Ecosystem, and North Cascades Ecosystem. At the time it was unknown whether the North Cascades could support a viable grizzly population, so in 1982 biologists recommended a full evaluation of the North Cascades Ecosystem as a potential grizzly bear recovery area.

The evaluation (1986-1991) indicated that, at the time, a very small number of grizzly bears still lived in the ecosystem and that there was ample secure and quality habitat to support a self-sustaining population.

In 1991, based on the results of the evaluation, federal biologists decided to restore grizzly bears to the ecosystem. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee formalized the inclusion of the North Cascades as a grizzly bear recovery area. A recovery plan chapter for the North Cascades was appended to the overall recovery plan in 1997. One of the four priority actions recommended in the North Cascades Recovery Plan chapter was to initiate an EIS to evaluate alternatives for how to recover grizzly bears in this ecosystem.

The government, led by the National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has now begun the EIS process and expects to complete it sometime in 2023 with a Final EIS and Record of Decision that will guide grizzly bear recovery in the North Cascades.

Can grizzly bears come back without our help?

Although there are grizzly bears in southwest British Columbia, their numbers are depressed because of habitat fragmentation, human development, and associated effects on bear security (e.g. poaching, human conflict) and genetic diversity. Because of barriers such as the Fraser River Valley and TransCanada Highway, the North Cascades Ecosystem is not well-connected to grizzly bear populations in the B.C. Coast and Chilcotin Ranges so there are no readily available source bear populations to recolonize the North Cascades naturally. On top of the connectivity barriers, grizzly bears are slow to increase in numbers because of their reproductive biology – they are the second slowest reproducing land animal in North America, next to the musk ox. All of these factors combine to make natural recolonization of the North Cascades by grizzly bears traveling in from elsewhere nearly impossible.

How long will it take to restore grizzly bears to the North Cascades?

Even with active restoration, it will take many decades before the North Cascades has a healthy grizzly bear population. Grizzly bears are slow to increase in numbers because of their reproductive biology – they are the second slowest reproducing land animal in North America, next to the musk ox.

Females are usually five to six years old when they have their first litter and then have an average of two cubs about every three years. Roughly half of these cubs survive to maturity. A typical female grizzly bear will have five cubs that survive to adulthood. Growth of the North Cascades grizzly bear population, under the best conditions, will be very slow. Biologists estimate it could take up to 100 years to reach the target population of 200 bears, and it could take longer.

Questions about Recreation in Bear Country

Is recreation compatible with grizzly bear recovery?

Yes, recreation is compatible with grizzly bears. As long as people use straightforward precautions and common sense in bear habitats to keep clean camps and avoid surprising bears along trails, there is little impact on either people or bears from recreation. Most grizzly bears try to avoid people, so an encounter or even seeing a bear is unlikely. Hundreds of thousands of people hike, fish, hunt, camp, and enjoy grizzly bear habitat every year with very few conflicts of any kind.

How will recreation be impacted by grizzly bear recovery?

For some, recreation in the North Cascades will benefit from grizzly bear recovery, giving individuals a rare chance to see grizzly bears and recreate in a place wild enough to support a grizzly bear population. For many visitors, this will enhance their experience, giving them access to a truly wild landscape with a full suite of wildlife. For visitors that do not want to encounter bears, the extremely low numbers of grizzly bears will rarely result in encounters. Front country recreationists will be even less likely to encounter a grizzly bear.

Since the North Cascades Ecosystem is already bear country, with a healthy population of black bears living there, recreationists should already be educating themselves on how to prevent human-bear conflict, and how to react to encounters. The National Park Service and Forest Service both recommend visitors take steps to store food and waste properly, carry bear spray, and educate themselves about bear awareness.

The landscape is already being managed for grizzly bears, so restoring grizzly bears is unlikely to impact road development, new trails, or other infrastructure supporting recreation.

Will grizzly restoration reduce access to trails and outdoor destinations?

There could be rare instances in which a trail is closed temporarily, usually because a bear is feeding nearby. The closure would help protect people and bears from possible conflict. But to date there have not been any permanently closed trails on any public lands where grizzlies are found. In the North Cascades it is not anticipated that any trails will be permanently closed or not maintained because of grizzly bear recovery.

Road closures and maintenance on national forests within the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone are determined predominantly by economic and water quality reasons. Protecting wildlife and habitat including but not limited to grizzly bears is another reason but not the main cause of closures. The current total number of national forest road miles in the North Cascades far exceeds the available funding to maintain them and poorly constructed or maintained roads have enormous impacts on water quality and fish. These impacts and related road management are not dependent on or directly impacted by grizzly bear recovery.

Can I safely recreate in grizzly bear country?

Yes, but like any other outdoor activity, you should be aware of your surroundings, store food and dispose waste properly, avoid surprising bears, carry bear spray, and know how to react if you see a bear and pay attention to its behavior so you can react accordingly. It is always best to travel with a group when in bear country.

That said, attacks are rare. Over a 32-year period, there were 2,275 grizzly bear encounters in the backcountry in Yellowstone National Park. 25 of these resulted in attacks. The risk of attack in the backcountry is 1 attack for every 91 backcountry encounters. The grizzly population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, of which Park is a part, grew from about 500 grizzly bears in 1991 to 1100 today. Those population numbers are orders of magnitude more than will ever be in the North Cascades in our lifetimes. 4.86 million people visited Yellowstone in 2021.

How can I avoid attracting bears to my campsite?

There are many specific things people can do to avoid attracting bears, either grizzly or black. Good sanitation is key to many of these. Odors attract bears to potential food items, and their curiosity can even attract them to items that are not food, such as petroleum products, beverages and toiletries. Carefully controlling odors associated with food and products which humans use helps prevent bears from being habituated to being near people. This means that we need to store our food, garbage, cooking gear, and toiletries where bears cannot get them. Once conditioned to human sources of food or garbage, a bear is dangerous. It may approach humans closely and come into camps or near homes to search for food.

There are a number of resources available for hikers, campers, horseback riders, hunters, anglers, and others living, working, or recreating in grizzly bear country. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee has published pamphlets and posters describing how to hike and camp safely in bear country. Ecologist and filmmaker Chris Morgan (formerly of Western Wildlife Outreach and the Grizzly Bear Outreach Project) produced this video with tips for hiking and camping safely.

Questions about how Grizzly Bears Interact with other Species

What impact will grizzly bear recovery have on other wildlife populations?

The EIS process will evaluate such impacts and display them in the EIS document. Grizzly bears are omnivorous, meaning they eat both plants and animals. In the spring, grizzly bears take advantage of vulnerable, young ungulates such as elk calves or deer fawns if they are available, as well as winter-killed carrion. However, in similar ecosystems to the North Cascades, they eat primarily vegetation, insects, and carrion.

Some “big game” animals probably will be taken. But deer, elk, moose, and other ungulate species are not expected to be a major food source, nor would the level of predation be expected to have a significant influence on overall ungulate numbers in and around the North Cascades based on what is known about other ecosystems with more robust grizzly bear populations.

What impact will restoration have on ranchers and domestic livestock?

An important part of the EIS process is to evaluate the potential impacts of each alternative on resources, economic activities and the public in the area. Ranchers can and do coexist with grizzly bears in Montana and Wyoming. Most grizzly bears do not prey on livestock. Conflicts with livestock are rare and when they do occur are resolved by capture and removal of the offending bear. There are measures that can reduce conflicts such as electric fencing is some cases. There are government agencies and cooperating NGOs who assist livestock owners with the financial costs of installing electric fencing when necessary and also to compensate livestock owners for any documented losses to grizzly bears. While there are incidents of grizzly bears preying on livestock, those are rare and often preventable without significant added costs to the rancher.

With education, bear awareness and some proper precautions, coexisting successfully with grizzly bears is easier than you might think.

Will grizzly restoration harm black bears?

Grizzly bears and black bears evolved side by side in many ecosystems. Although grizzly bears can eat black bears, they generally learn to avoid each other. When grizzly bears are absent from a system, black bears tend to occupy spaces the grizzly bears previously occupied. When grizzly bears are restored black bears learn how to avoid grizzly bears, cede some key habitat to them, and find other food sources to survive.

Questions about the Recovery Process

What is an Environmental Impact Statement? How does it work?

An Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is a document that evaluates and discusses potential environmental impacts that would occur as a result of taking an action. An agency must look at the impacts of its proposed action, as well as reasonable alternatives for accomplishing its objective, in this case restoring a self-sustaining grizzly bear population to the U.S. portion of the North Cascades Ecosystem.

The EIS process is completed in the following ordered steps: Notice of Intent (NOI), draft EIS, final EIS, and record of decision (ROD).

The Notice of Intent is published in the Federal Register by the lead federal agency and signals the initiation of the process.

Scoping, an open process involving the public and other federal, state, tribal, and local agencies, commences immediately to identify the major and important issues for consideration during the process.

Public involvement and agency coordination continues throughout the entire process.

The draft EIS provides a detailed description of the proposal, the purpose and need, reasonable action alternatives, the affected environment, and presents analysis of the anticipated beneficial and adverse environmental effects of the alternatives.

Following a formal comment period and receipt of comments from the public and other agencies, the final EIS will be developed and issued. The final EIS will address the comments on the draft and identify, based on analysis and comments, the “preferred alternative”.

After the final EIS is complete, a record of decision is signed by the agency (or in this case joint agencies) thereby allowing the selected alternative to be implemented.

Who is coordinating this process?

The National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are the lead agencies; the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) are cooperating agencies. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) (comprised of all the above and four state agencies) will coordinate and oversee recovery actions and provide input to the North Cascades process.

The Province of B.C. also provides input to the EIS process and sovereign Native American tribes and nations will participate through government-to-government consultation. Other cooperators may be identified in the future.

Do a majority of people support grizzly recovery?

A clear majority of Washingtonians support grizzly bear recovery. A 2016 poll asked specifically about efforts to help the declining population of grizzly bears in the North Cascades to recover, 80 percent of voters say they support these efforts to just 13 percent of voters oppose them. Notably, this overwhelming support extends across gender, generational, regional, and even partisan lines – with 89 percent of Democrats, 70 percent of Republicans, and 74 percent of independent voters backing these efforts.

How can I get involved with this process?

Review our Privacy Policy

Thank you for visiting the Friends of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear website! This website is owned and administrated by Conservation Northwest. By visiting this website, you are accepting the policies described in this Privacy Policy.

This Policy discloses the privacy practices for https://www.northcascadesgrizzly.org/, as governed by Conservation Northwest, and applies to information collected by this website.

It will notify you of the following:

- What personally identifiable information is collected from you through the website, how it is used, and with whom it may be shared.

- What choices are available to you regarding the use of your data.

- What security procedures are in place to protect against the misuse of your information.

- How you can correct any inaccuracies in the information.

Information Collection, Use, and Sharing

Conservation Northwest is the sole administrator of the information collected on this site. We only have access to/collect information that you voluntarily give us via the email sign-up for the Friends of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear coalition. We do not sell or rent this information to anyone. (Note: If you are looking to receive general communications from Conservation Northwest, please visit their website instead at https://conservationnw.org/join-us/)

We will use your information to send correspondence that you have specifically signed up for or requested to receive from the Friends of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear coalition. We will not share your information with any third party outside of the coalition.

Your Access to and Control Over Information

You may opt out of any future contacts from us at any time. The easiest method to do so is to contact Conservation Northwest directly at info (at) conservationnw.org or 206-675-9747. You can do the following at any time by contacting us via email or phone:

- Change contact preferences, including unsubscribing from all or certain emails.

- See what data we have about you, if any.

- Change/correct any data we have about you.

- Have us delete any data we have about you.

- Express any concern you have about our use of your data.

Security

We take precautions to protect your information. When you submit sensitive information via the website, your information is protected both online and offline.

Wherever we collect sensitive information (such as credit card data), that information is encrypted and transmitted to us in a secure way. You can verify this by looking for a lock icon in the address bar and looking for “https” at the beginning of the address of the Web page.

While we use encryption to protect sensitive information transmitted online, we also protect your information offline. Only employees who need the information to perform a specific job (for example, processing gifts or customer service) are granted access to personally identifiable information. The computers/servers in which we store personally identifiable information are kept in a secure environment.

Analytics

We do not directly collect “cookies” on this site. We do, however, utilize standard Google Analytics services to track the number of new website visitors, return visitors, and the length of time you spend on a particular page within the website. Other information such as screen resolution, computer operating system, language, and browser type will be utilized one time to automatically format our website to the optimal display based on your device. Learn more about Google Analytics at this website.

Sharing

We share aggregated demographic information with our partners and advertisers. This is not linked to any personal information that can identify any individual person.

We may use an outside vendor to ship orders or send mail, and a credit card processing company to bill users for gifts, goods, and services if applicable. These companies do not retain, share, store, or use personally identifiable information except for the purpose of providing these services.

Links

This website contains links to other websites, including social media platforms. Please be aware that we are not responsible for the content or privacy practices of such other sites. We encourage our users to be aware when they leave our site and to read the privacy statements of any other site that collects personally identifiable information.

Donor Privacy Policy

The Friends of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear coalition and the sole administrators of this website, Conservation Northwest, value the privacy of our constituents. No donations are collected on behalf of the Friends of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear coalition or any of its members through this website. The type of constituent information that we collect and maintain includes:

- Contact information including name, address, telephone number, and email address

- Information on events attended, publications received, and special requests for program information.

- Information provided by the constituent in the form of comments and suggestions

If you have any questions about this privacy policy, please contact Conservation Northwest via telephone at (206) 675-9747 or via email at info (at) conservationnw.org